To conclude the Art on Hennepin interview series, we had a moment to interview Hazel Belvo, one of the founding members of Women’s Art Registry Minnesota and a renowned artist from Minneapolis to New York.

Thank you for sitting down with us today. To start, will you give me a little background on yourself?

Briefly, I was born and grew up in southern Ohio on a horse-powered farm. My early art history, I went to Ohio State University, but it was the beginning of the McCarthy era and I had to leave because the politics at that time were so foreign and difficult for me.

I spent some time at the Dayton Art Institute then left Ohio. From there I went to New York when I was 25, where I studied at a new school but the whole art world of New York was my really strongest and deepest education. I had a lot of opportunities in New York to become more known in the popular art world, but for some reason, well, for lots of reasons, it never appealed to me.

I don’t like the concept of a star in the art world because one time Henry Geldzahler, who was the curator for modern art at the Met, came to look at my work in my studio. I made the appointment during the time that my little son was taking his nap. We had a glass of wine, and we were talking, and he said to me, ‘I can make you an art star.’ And I didn’t say anything right away, so he said, ‘But you have to do everything I tell you, and it doesn’t involve that kid do you have any other room, or the Indian you’re married to. Now how about that?’ And so, I said, ‘Oh, I can’t. I couldn’t do that. I won’t.’ He hadn’t even looked at my work when he said he could make me an art star. That’s the reason I didn’t answer him at first, because I was waiting for him to look at my work, but he never did.

But even after that, for two years, we lived in Rhode Island because George [Morrison], my husband, was at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), and I was studying for my master’s degree at Harvard’s Bunting Institute. It was the perfect situation because my life went on between Provincetown, Boston, Cambridge and New York, and Rhode Island was an easy drive to all of them. I was right in the middle of it all and exhibiting widely.

It was at the Bunting Institute when I was introduced to the second part in the feminist movement. The people who were writing and thinking and promoting feminism. It was really exciting for me and quite a difference from the group I had in New York, which was so male oriented. It was great for me to be at the Institute, and I was like sitting around the table with twenty women who were doing incredible things; writers and doctors and artists. It was really great.

When did you make your way from the coast to Minnesota?

I lived in the world of New York, Boston, Provincetown and Rhode Island, and I had established myself with places to exhibit and places that knew me and my work and responded to me. I was teaching full time and my oldest and youngest son were both in the Moses Brown Preparatory School. But in 1968, my oldest son was diagnosed with acute myelogenous leukemia, and given six months to live. But he had more than six months. He kept living and being treated and while George was teaching at RISD, and I had this good full-time teaching job, which allowed my boys to go to that school and the Moses Brown school was so good to him. They made such great allowances for my son who was ill. We had just finished flipping two houses, so we were established.

But, and this came as a total surprise to me, one day George said to me that he had gotten an offer to teach at the University of Minnesota. And he asked if I would come with him. And I said, right away, no, because of everything I just said. The house was just finished, the boys were in a good spot and I was right where I wanted to be. But then we talked to Joe, my oldest, who was 15. He did not like his doctors at the Rhode Island Hospital. They were very conservative Catholic guys, and they didn’t like a long-haired kid with a guitar and a mind of his own. So, then I did some research and I found that the Masonic hospital in Minnesota was the best place the top place for a child with leukemia in the country. So, for that reason, we all agreed that we would move to Minnesota. From the time George got his letter to the time we moved to Minnesota was two weeks. We sold both houses, packed up and left our lives on the East Coast behind in two weeks.

When did your time with Women’s Art Registry Minnesota (WARM) start?

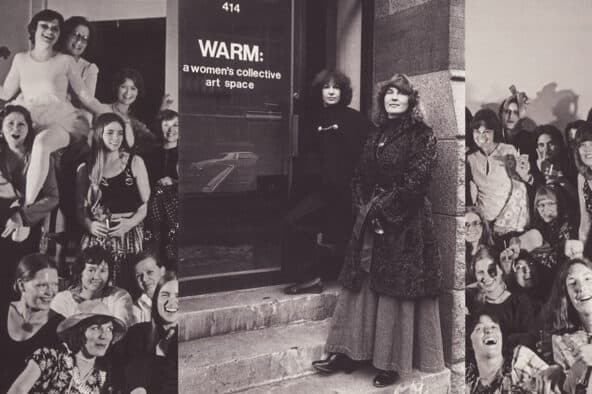

I think it was in 1973, I met a group of women, I think they were students who had just graduated from McAllister, who got together and had open meetings in different artist studios. And I started going to those meetings and the meetings were not so much about feminism as they were about art, but they quickly became about both. And one day we were having a meeting, and one woman stood up and said let’s start a gallery. She said, ‘Whoever would like to start a gallery, stand up,’ and forty women stood up. And there were a lot of women who stayed seated because I think during those times it was radical to make a commitment toward feminism—it was a pretty radical thing to do out here, not so much on the East Coast. And I was accustomed to it because of the Bunting Institute. So anyway, it was very exciting and that’s how we started. You know, we had committees to find a place, a committee to write a constitution, a committee for everything.

The registry was held by the gallery and every woman who named herself as an artist could put slides of her work into the registry. And so the registry grew; there were lots of women around the state with their work in the registry. There were certain dues if you were exhibiting in the WARM gallery, but you were automatically a part of WARM if you entered the registry. If you paid dues, something like $15 a year, you could feature your work in the gallery.

And the gallery was beautiful. It had a mezzanine that opened onto one gallery, and through a big door you could find another. Everything was white and the floors were polished oak wood. We had a back room for materials we needed to run a gallery and a side room that had been a vault for the businesses that were there before we took over.

Did you ever run into organizational trouble, governing collectively by committee like that?

We did, but one thing about WARM is I think we did the organization of it really well, but it’s very hard to govern collectively, because there has to be a lot of discussion. The meetings were long, and they sometimes got very weary. Some women couldn’t really take it very easily to come to a decision because everybody, I mean, being powerful women, everybody had very strong ideas. But we broke out, we had committees for things, and the committee would agree on something and bring it to the whole group. And once a month we met as a whole group in our chairs. And we always met in a circle and there are some things we could have done better and more of but we were limited by financial issues. But I thought we were very successful as a group when we stayed making the decisions in the in the group and we had.

But we did come to a point where it was decided that we would get a director; I think we’ve got a grant or something to get a director and then the director made some decisions that I personally was opposed to. I think that is what happened to WARM in the end. It was a time when you could get money for a lot of different things, and so the director would apply for grants to do these things, but then we would be beholden to the grantor. I remember we had a meeting to agree on the path forward. I was in favor of the group of WARM members holding our power and I remember saying we would be all right as long as we could pay rent, which we paid with our organization dues, and kept the gallery open without relying on these grants because the grants were going to dry up. And they did. And so WARM closed their doors, I think that was in 1991.

WARM was based out of the Wyman building, is that correct? What was it like being in the Wyman during the height of all this art and creation that was happening while you were there?

We were the first ones, we started it all in the Wyman Building. Yeah, it was a I was on the committee that found it. It was a dry goods store, and everything was sort of black and gold. I remember the walls and woodwork and yeah, but we did some really wonderful things there that came out of the WARM collective idea. We had some great galleries there. Once, we decided to have a compete gallery exhibition called “Here Today Gone Tomorrow,” where every work of art that was a part of the exhibit would just be made for that show, and then it would disappear. So, we filled the gallery with amazing artwork and ensured it was all gone the next day. Oh, we had great openings too. We could all bake, so we would bring carrot cakes and fresh bread and wheels of cheese; really make everything welcoming.

We had less savory encounters, too. People came in off the street and were offended by “communist” ideas and one time, I went to the Studio Arts building over at the [University of Minnesota], and I was walking down the hallway past all the professor’s offices (this is before they had any women on the faculty) and there was a WARM poster with WARM marked out with black pen and beneath it was written WORM. WORM! I was so furious when I saw that. I mean, at the university? But you know, people, especially some of the male professors at the U of M, were angry because they couldn’t be part of WARM. They said we were discriminating. It was a mixture of things, but it was an event of its time, and it was, I think, important.

Did WARM and other feminist collectives like it face discrimination like that often?

I think it was more the fact that we were shaking things up. You have a collection of male professors that you’ve upset so much they’re defacing your posters, you know you’re doing some good work.

I think that George finally did come around. George, because he was part of that faculty, began to see that the dialogue and the attitude was so destructive. And I don’t know whether to count that to his being Native American, but I don’t. I just think that was how he was. He had to be convinced, though, but he came through. Finally.

We’ve heard about the monthly art walk from some of the artists we’ve interviewed for the Art on Hennepin series, did WARM and the Wyman participate?

Yes! WARM had a hospitality that was different. And actually, when I lived in New York, every Tuesday night there were openings and the way the artists turned out and the way they were welcomed by the galleries really shaped the way we did it at WARM. Like I said, we always would get a big wheel of

cheese and big loaves of bread or big carrot cakes or something. Oh, and boxed wine. A nice charcuterie spread.

And for whomever had a show in the gallery, we always had openings. I think the openings might have taken place on nights of the crawl. But most of the members would come. I have some great photographs of shows that I had, there were so many people; it was always crowded. And my son had a band, so when we held an opening, his band would play. We would lock the doors and dance until two o’clock in the morning.

As an artist that is still active in the community in the metro and Greater Minnesota, what are your thoughts on the art scene now compared to the art scene then?

I mentor artists all over the country and Canada, pretty much from the East or West Coast and the Midwest, so I would always be able to be very articulate about what was going on, but since 2018, I have done a lot less in the community. So, I can’t really say too much about the last five years. But, if there are a couple of things that I’m really disappointed with; one of which being that when I first moved out here in 1970, there was so much awareness of and energy being generated by the art community. A lot of people were on the scene. A lot of artists from the East Coast were coming here. The Midwest gets the term flyover, but people stopped here. We had guest rooms in the 1970s that were always full. The Tribune had a double page a week that listed everything going on in the arts. But now, there’s no one place to find anything listed anymore.

MCAD has changed a lot, too. When I was there, I helped develop the graduate program. Now they have several different graduate degrees, not all of them involving making. Times are different. There are few places that are forming a content gallery that adhere to the older formal aspects of exhibiting and sharing. It’s more centered in a retail environment.

But part of that could be me, too. Because in the last five years, my wife Marcia and I have really relaxed. We go someplace twice a week, maybe. I mean, next Monday I’ll be 89. All through the years we have had so much energy and we were right on top of everything, and now we don’t do that.

Where is WARM today?

WARM doesn’t exist so much as a developed group anymore. It’s a little confusing, because WARM initially stood for Women’s Art Registry Minnesota. When the gallery itself closed, the WARM registry continued and it had the director, and it changed the name and it wasn’t the registry anymore, it became Women’s Art Resources Minnesota. By this time, I was no longer a member. I think for a time they had an office, but there was minimal staff to support it; one person who was the director and maybe a board, too. Nowadays, there is still a web page, but I don’t think it gets updated.

Do you have any parting thoughts you would like to share before we conclude?

I think WARM was really wonderful. It was better to do it than not; it was complex, it was demanding and I think it took a certain combination of personalities to accomplish what we did. And if there is one thing that came out of WARM that I think affected a lot of people, and certainly the women I’ve mentored but also several of the men I’ve mentored, I think it has helped them grasp the concept of art beyond what was taught by the men who ruled the art world when I was in New York.

There is a certain mythology about the art world that they established back when New York was the art world’s capital back in the 1940s, 50s and 60s. There’s this mythos that an artist has to work consistently all the time, in a track that you will develop at a consistent rate. That you need a developed look or brand that when people see a piece they recognize it as yours. But WARM taught me and I taught my students that art comes in an ebb and flow, and you shouldn’t force a brand just because that is what you are taught you should be doing. That’s the legacy that I’ve created and it’s astounding to me.