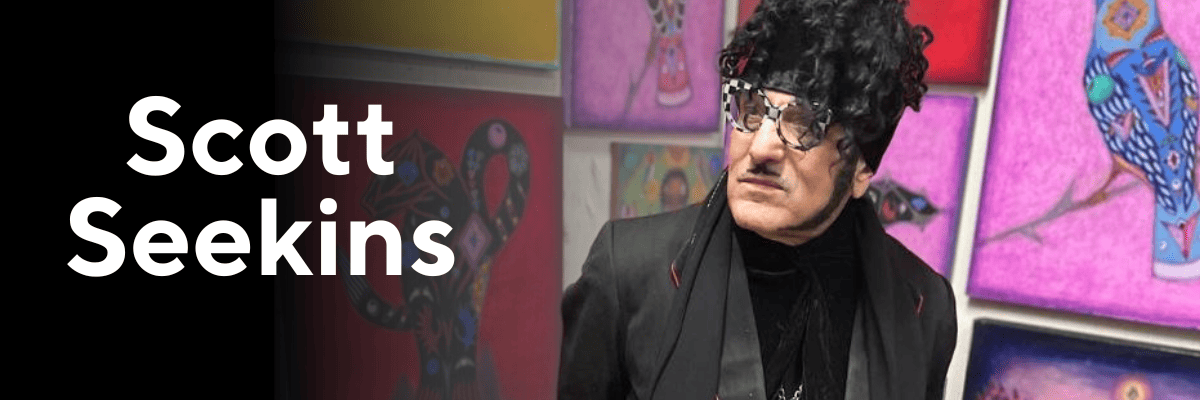

The Art on Hennepin Interview Series would not be complete without interviewing Minneapolis artist Scott Seekins, a long-standing icon of the local art scene who has lived through its many iterations. As part of the exhibit Art on Hennepin, which is featured in the Jack Links Legend Lounge until January 7, 2024, Hennepin Theatre Trust had the opportunity to meet with Seekins to learn a little more about the icon in black and white.

Thanks for being here with us, Scott. To start, will you tell me a little bit about your background? What is your origin story?

Well, that’s murky and cloudy. I was abandoned as a child in Lacrosse, Wisconsin. I was born there, and when I did the DNA test, I looked for my people but never found my parents. It must have been bad. No father, no name, no nothing. But about my mother, they found out she was 24 and went to Lacrosse to have the baby and then gave it up. I always say I was left down by the Black River amongst the rattlesnakes. That’s the legend; it’s better than the real story, I’m sure, but I don’t know who they were.

From Lacrosse, how did you find your way into the Minneapolis art scene?

I had wonderful adoptive parents. My mother was probably the nicest mother I ever met—she treated me nicely every second. They took me from the rattlesnakes and raised me in South Saint Paul.

My father’s family was in the meat business, cattle buying and stuff. He wanted me to get a job down in the stockyards. It was so horrid down there. I once got a summer job there in the hide cellar; that’s where you work with these incredibly stinky hides and once they touch you, [the stench] is on you for days. My only other option was pork kill. Now, if I’d been a hockey player, I would have got packaging, that would have been okay, but for pork kill you’d get these boots that go up to your waist and then you’d go in and the pigs would run out, and you’d… well, you get the idea. I would never eat pork again.

So, when my mother said, ‘Do you want the house?’ I said, ‘Nope, I’m out of here. I’m going to art school.’

I had hoped to be a chemist, but I couldn’t do the math, so I ended up going to MCAD [the Minneapolis College of Art and Design].

What was MCAD like while you were there?

It wasn’t as expensive as it is now, it’s really changed since I was there. It was still highly ranked in the nation, though. When I was there, I was on probation the whole time. I’m kind of proud of that D-plus average; they flunked people out like you would not believe because they didn’t need the money. All these teachers were real aloof and snotty, but good. They were all from Yale and really good teachers, but they were mean.

You took three buses to get to class at 8:30 in the morning and while students were setting up their stuff, the teachers would come out and just tear apart your work—sometimes literally! Then you would leave at 6:30 at night or something and go home, work all night to get these color problems and assignments done. Everyone was struggling, doing speed all night to stay up and finish in time to go back and repeat the whole process the next day.

The rule was that if you don’t have work, you don’t come. Miss three times, flunk. It was rough. I remember one of those teachers took my design problem I was working on. He came up and he was

holding it, and he said, ‘You’ve been drawing well in the class, but your subject matter is terrible. We don’t like that.’ And then he said, ‘You’re going to flunk, Seekins.’ And he took my piece and he crunched it and threw it in the basket. I just laughed at him and went to the bathroom and started crying. I was really scared, you know? I thought I was going to flunk, and it went on like that for two years

In my last year, one of the teachers—he was from New York, very pretty, he smoked cigars instead of a pipe, very elegant—was walking around, judging our color studies. And I wasn’t good at color, and I thought I was going to flunk out for sure. He said, ‘No one really got this problem. It’s all not good. I’m going to have to take it all down.’ But then he stopped and said, ‘There’s only one exception.’ Mine. It was like a light came on in my brain and I suddenly understood color just like that. It was a defining moment, and I went from a D-plus to a B-plus in that class.

What made you stay?

Just because I told my parents I had to go to art—that was the last thing for me. Art school. I didn’t have a job otherwise, and I thought maybe if I took graphic design, I could get a job in advertising or something. But I was low on the list of prospects.

Getting into the professional scene took a lot of years, most of the 70s. That was the first of the painting I did. 1972 was my first show and 1975 was the next. Before those exhibits, I’d never been in a show, and it’s like you’re not only claustrophobic, but that people were looking right through your clothes. I remember freaking out and running away and never coming back—I left my art there and didn’t pick it up at all. But then a couple months later, I got back on my feet and started doing more. I eventually adjusted to the scene.

What was it like back then, living in the art scene with so many other creatives?

The art scene? Well, when I was at MCAD, I didn’t know exactly what I was doing yet. I was a good draftsman, but I wasn’t really into painting yet until I got out and then I decided to get into it. Once I discovered the art scene, though, I realized how vibrant it was. Really rich with some of the best art at the time. I think nowadays it’s more about money. There are still some interesting photographers out there, but it’s less about art these days.

There were a lot of interesting people and places on the scene, but Block E was the place to be. I think there were 14 galleries on Block E in its prime, and they all had a big art walk once a month. This was the height of the local scene. Individuals and corporations were buying, even some wealthy private collectors, and they loved this art walk. You could visit all those galleries and they had all these great displays up floor after floor. There were even more outside of the galleries, in unconventional spaces—like the first Rifle Sport. On the West Bank, there was the New French, Black Forest, Fort Mango—all these bars that would double as galleries. The New French was my favorite; I was their first and last customer.

It was really the prime time. It was a wild time, it was fun. I call it the first, and longest, of my happy times.

Since then, have you only made art for a living, or did you have a side job?

Yep, I have no job skills. I went out once to find a part time job with a list of a hundred jobs I was going to try for, like rust proofing and all kinds of weird things. Just part time to help. I went through all one

hundred. They didn’t just say the typical Minnesotan ‘We’ll call you later’ (which is a no), they went, ‘Door’s that way.’ They saw me in the all-white or black outfit, and it was over.

When did the white and black start?

Right at the tail end of art school. Maybe 1968, or sometime around there.

How did you come into that identity, with your black and white rotation?

That’s a good story. When I was taking the bus back and forth from South Saint Paul to MCAD, it took two or three buses to get there and it had really long layovers. So, I went shopping in Saint Paul. It was really a cool place. It had all these shops from the 30s, 40s and 50s, and I saw this one shop, a clothing store run by a Polish gentleman, that had such unique looking white suits and black frock coats. Very 19th century; hats and celluloid collars and everything. I went in there and I fell in love. I had been looking for something, I didn’t know what I was looking for, but I was looking for something. I wanted a signature look.

When I went in for the first time, he was with a customer, and he yelled at me to get out. I didn’t understand, but I left, nonetheless. It wasn’t until later I found out that, traditionally, the first customer of the day is gold, and you treat them as royalty, and don’t help anyone else during their time. So I made sure to be the first customer the next time I went.

When I arrived, the owner asked me, ‘Are you a student?’ And I said ‘Yes.’ And he goes, ‘You’re studying to be a rabbi, right?’ and I lied and said ‘Yes.’ And he gave me great bargains, showed me how to sew buttons. We became good friends after that.

What is life like as a recognizable public figure? There are Star Tribune articles about you, entire blogs dedicated to seeking Seekins; how does it feel to have spent so long as an icon of the Twin Cities art community?

Sometimes, a lot of the time, it’s good—a lot of popularity. Who else can say they’ve been relevant for the last fifty years? In fact, some of those people that said, ‘The doors that way,’ I started running into them at my art shows. I remember seeing one at an opening, and he recognized me and said, ‘Oh, I didn’t realize you could do all this art, it’s kind of nice.’ He goes, ‘Do you do this for a living now?’ He starts asking all those typical dumb questions, and finally I said, ‘I’m meeting some patrons that are interested in art, if you don’t mind.’ Then I just pointed to the door. It was an exchange I had waited my entire life for.