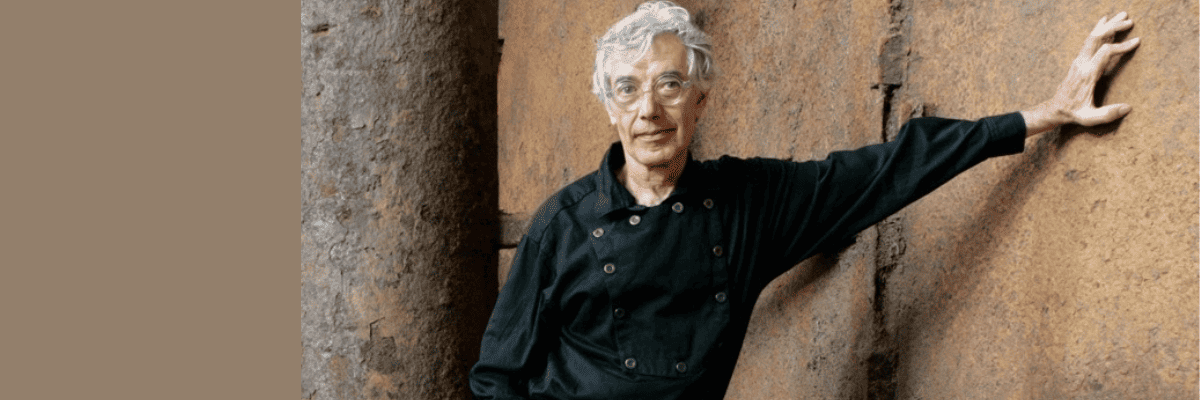

The Art on Hennepin Interview Series: From Hennepin to Hawaii with Tom Sewell

As part of the exhibit Art on Hennepin, which is featured in the Jack Links Legend Lounge until January 7, 2024, Hennepin Theatre Trust had the opportunity to sit down with icon of the 1960s Minneapolis art scene and founder and curator of the Bottega Gallery, Tom Sewell.

Hi Tom. I think we can jump right into it, thank you for joining us so bright and early Maui time.

Happily! I’m really excited about this. You’re bringing back memories from 60 years ago. It was one of the highlights of my life.

Just to get the ball rolling, will you introduce yourself and give a little bit of background around your time on Hennepin? We spoke earlier on your time at Dayton’s, since the Trust has some of the surviving figurines, could we start there?

Yes! Back in the early ‘60s, I was working at Dayton’s department store. I had just returned from a trip to Brazil where I live for a year, and one of the guys in the display department had started a gallery on Hennepin Avenue in the space, no name. His name was Terry Riggs (no relation to Dudley). He was kind of a character, he was pretty weird. But he started this space, and I decided to go up and help a little bit. I helped him paint the walls, cleaned up the space and so forth, and then he disappeared. Never showed up again. The mystery of Terry Riggs; it’s unexplained. He’s an enigma. But the rent was paid through until the end of the month, so I took it over.

The building was owned by Joe Piazza, who ran the Café de Napoli on the main floor, which had beautiful booths and great murals of Napoli. So, I paid him the rent each month, took over the space and little by little expanded until it was in a huge formal affair on the whole upper floor of the building. To walk in or walk out of the second story you would enter right by the Café de Napoli office there, and there was a glass window, and I was able to put a piece of art in that window each month so people could see that there was a gallery upstairs. And later I somehow managed to score some fabulous letters. Wooden letters that I gold-leafed to spell Bottega gallery in traditional style lettering. I don’t know how I ever did that. But we got them on the building, and it looked beautiful. So, there I was, 22 years old. Had this art gallery, and I hardly knew anything about art, but I proceeded and had a young woman working with me, named Rita. Rita Johnstone was my assistant and the two of us created this gallery. Little by little, it got famous.

The two things that made us famous were the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s big biannual show and the strange exhibitions we held. At the biannual show, they rejected a lot of work, so I decided to do a salon that accepted all the rejected work. This turned out to be a brilliant move because all the artists that were rejected wanted to participate. I charged two bucks, and they came up, dropped off their work and we had a humdinger of a show. It was really fun and overnight I got to meet all the artists. They all came up and we had a big exhibition, it got super coverage; the Star Tribune always came up. Their journalists really loved the gallery. Overnight, the gallery became famous.

I mean, we didn’t make any money. Looking back now, it seems like my main job was just to figure out how to pay the rent each month, but this was the early ‘60s—things were happening, a lot of exciting art was going on and I was right there in the middle of it. There were no art galleries in downtown Minneapolis at that time, not really. There was a one gallery that was actually at the art supply store, Kilbride Bradley. So they had a gallery space, but it wasn’t a full on a gallery, it was an art supply store. The other gallery was owned by Gordon Loxley, who was an absolutely animatic, funny, wonderful fellow; a good friend. He had a hair salon, the Red Carpet, on Nicollet Avenue with a gallery in it. So that was kind of it for downtown Minneapolis. A little later, Felice Wender came along at Dayton’s and opened Gallery 12, which was fun to have that going. But for a long time, Bottega was the gallery for downtown Minneapolis. This is ‘62, ‘64. Something like that.

It was pretty interesting. It was. We had everybody come up to the gallery. I mean, really interesting people. People came from Wayzata, came from all over Kenwood, from Saint Paul. People came up from Stillwater. A guy named Raymond Degania came in and said he was a hand dancer. I asked what that was and he simply replied that he danced with his hands when I said, well, let’s do a show. I put together a poster and sent out flyers and went to the Star Tribune. Raymond sat in the middle of the room and danced with his hands. We became famous for things like that, all the eccentric exhibitions we put on.

Sort of on that topic, how did you garner press attention like you did? This little gallery up above Café de Napoli generated so many news clips, how did you get the word out about the gallery; did you have ties with the Star Tribune? How did you drum up publicity?

Oh, well my idea for publicity was twofold: number one I always did a great graphic. I’ve spent a lot of money and a lot of time putting together really good graphics. I’d make a deal with a local printer that he would print the graphics up for me and I’d give him a piece of art. Then I’d send these graphics to everyone on a huge mailing list.

Then, I’d get out my little Honda 50 motorcycle or in my Daimler motor car and drive down to the Star Tribune. In the cold season, I would wear a giant raccoon coat and a funny hat to boot. I’d walk in, striding down the aisles of all the journalists and hand out these flyers and tell them what we’re doing. That became a big hit, so every show I would do that; send out the flyers, go down to the Star Tribune and do the walkthrough. That helped a lot. Also, the journalists would visit the gallery and we’d have lunches together and we’d sit downstairs for lunch at the café or bring it up to eat in the gallery. We just developed a really great rapport with everybody, so the word got out.

Looking down Hennepin Avenue today, it’s not like it was in the ‘60s. So much has changed with communication. If you’re going to do a show today, you need to have a social media presence to use as a communication platform—the way you did this is almost magical to us today. It’s fascinating that you could put on a show the way you did. How did you find your way running a gallery?

I didn’t really have anybody to tell me what to do. We just made it up as we went along and we saw what worked. I, of course, was extremely influenced by Martin Freedman and Mickey Freedman at the Walker Arts Center. I never really went to college; I had a year at U of M but I didn’t get anything out of it—I quickly dropped out. For me, the Walker Art Center was like my university. I’d go up and see the shows, see the artist, see the excitement, the graphics, the bookstore, the gift shop, everything. So that was an inspiration for me. The other thing is that my older brother was very much involved in the world of art and design. He was a famous wallcovering display man, and he would do all sorts of interiors staging houses, so it was a good influence on me in terms of graphics and color and design and things. I could always count on my brothers Don and Steven Sewell to help me with the gallery, and my mother would come up and serve tea. My father would help me build things, but he wasn’t that interested in my artwork.

Where did you get the name Bottega?

This came from when I was when I was working at Dayton’s. I was in the display department, and I heard the guys at the table at the lunchroom in the cafeteria talking about Brazil. This was in 1960 and Oscar Niemeyer, the architect had just created a new capital city for Brazil. And they were saying how people were making fortunes overnight down there, that perked my ears up. They talked about one guy that made $100,000 in a week, a fortune overnight, and I thought that was great. So, I got my mother to drive me to Wichita, Kansas because I heard that Brazilian ranchers bought Cessna airplanes from the Cessna Corporation in Wichita, where they were made and that they had to fly their planes down to Brazil, so I thought I could get a free ride. Mom drives me down into Wichita from Minneapolis in a black Ford convertible, and she dropped me off and I stayed there for six months trying to find a ride. I eventually got a ride and went all the way to Brazil, hitchhiking in this little one engine plane; took 12 days. It was quite a trip, it was an amazing adventure, but when I was in Wichita, I went to the university there for a film one night and I met some guys that had a gallery that was called the Bottega. And I went to see them the next day, and I worked out a plan where they let me stay in the gallery. I could sleep there if I kept the floors clean. So I took over a closet and made a little apartment out of it. And I stayed in this Bottega Gallery for four or five months.

I got to know these three artists and their work and so forth, and I was quite impressed and moved by that experience. So that’s the name I gave my gallery in Minneapolis several years later, when I came back from Brazil and opened the gallery on Hennepin Avenue.

With your Brazil-inspired gallery picking up momentum, did you have any standout visits from celebrity artists?

I’ll tell you a little story about Marcel Duchamp and my father.

Rita and I were sitting one day and we’re really having a hard time trying to figure out how to get people in the gallery and what to do and how to pay the rent—God, it was hard to pay the rent each month! So, I’m putting out the little catalog, a description of six exhibitions that we were going to do and invite artists to participate. One of these shows was of pregnant women, we had a show of insects, we had a show of landscapes, a whole lot of shows. But one of the shows was a show of found art, readymades and, while I knew little about Marcel Duchamp, I of course I knew about his urinal. The fountain that he signed “R. Mutt” and entered into the salon in Paris and was rejected. So, I took a photograph of the urinal, put it in the catalog, and I dedicated the show to Duchamp.

Then I got this idea; I said let’s send Marcel Duchamp a letter. So, we found his address someplace—those were the days when addresses were easily accessible—and I sent him a letter. ‘Dear Mr. Duchamp, we’re having an exhibition of found art. We really like your work, would you be willing to enter a piece?’ Didn’t think any more about it.

Lo and behold, a week or two later comes a letter, from Duchamp. He said, ‘I was thrilled to receive your letter, your show sounds wonderful. However, I don’t make art anymore, but I’ll enter myself in your show. I’ll call you when I come to town, I’m coming to the Walker Art Center, they’re doing a show of my work, the Mary Sisler collection.’ A month later, I got a phone call and it’s Duchamp. He’s up at the Curtis Hotel, he says, ‘I’m here with my wife, Teeny, you can come and pick us up.’ So, I jumped in my Daimler and drove to pick them up.

Teeny gets in the back seat and Marcel sits down next to me; there he sits with his famous profile and it’s very distinguished and we drive to the gallery. We go upstairs and Marcel looks around the gallery with me; we look at the found our show this up. I’ve got pieces of billboard I’ve got dolls and tin cans; I’ve got crazy stuff that we’ve collected, all sorts of detritus. He asked me a few questions about myself and if we’re selling and so forth and we sit down. And there’s a stack of my erotic colleges sitting on the floor, I was just taking a show of my work down. Back in 1960, I would go down to Shinder’s, buy those sorts of magazines and I would take a razor to cut certain parts out of them to replace the background, like lips from a fashion magazine, things like that. They were pretty wild. But Duchamp said it was the freshest art he’d seen in years.

He asked if he could have one for myself, and I said certainly. Then he said, ‘Could I have one for my friend Max Ernst? They remind me of what he did when he was young’ [Ernst was a painter and sculptor, Duchamp’s contemporary and longtime friend]. So, I get him two of my collages and then he turns around and signs my necktie, making me a readymade.

We spent the whole rest of the day and evening till about midnight in the hour, and we sat down for food from the café, we played music on our old wind-up phonograph. We watched the people on the street from the balcony. It was like we were watching an old-time movie. We were talking, laughing, thinking it was so fun and Marcel’s wife started to cry, and we said, ‘Teeny, what’s the matter?’ She said, ‘I’m having so much fun. It reminds me of when I first met Marcel.’ It was a special evening.

And Marcel ended up inviting me to come to New York, which I never did, I went to the West Coast instead and ended up staying. I often wonder what would have happened if I’d gone to New York in 1964 and been under his wing; it could have been a whole thing for me.

But, on the other side of the story, my father came up to see my erotic art show a little bit before that. And his impression was quite different from Marcel’s. He said, ‘Looking at your art makes me think that I was stabbed in the stomach and someone is turning the knife.’ He was appalled by my work. He did not support it at all. So, I thought it was a good lesson here. You know, you don’t necessarily need the support of your father or your parents. You can find other mentors. And Marcel became my main mentor for my entire life.

Standing in the gallery above Hennepin Avenue and being encouraged by a man of that caliber, it meant so much to me. I think it was like a magic wand that gave me the confidence to do anything I want and I don’t need to have everyone’s approval. I’m okay with criticism now. I’m okay with being the only one doing art my way. Duchamp taught me to be myself.

Holding events like your Minneapolis Salon des Refusés, did you ever get into conflict with Mia or the Walker?

They seem to like it. I never had a conflict, and as a matter of fact, in one of the shows, I entered one of my erotic colleges, framed. I called it Marsha, Marsha, Marsha, and it was sold to Johan Vandermark, who was a curator at the Walker, and I felt pretty good about that.

No, I had no conflict with any of the museums. As a matter of fact, in my early days I worked at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, when I had just come back from Brazil, and I went to an exhibition at the Institute. And it blew me away because it was displayed so beautifully. The walls were painted very interesting colors in the Rembrandt Room. The walls were covered with fabric that had been glued to the walls, back side facing out, so it looked like a 15th century wall covering. And I said, ‘who is responsible for this?’ I was told Carl Weinhardt is the director in all of this. So I found out from the guard where his office was and went down and knocked on his door and I said, ‘Mr. Weinhardt, I’m your new assistant, and I’ll be working for you for nothing. I think what work you’re doing here is amazing. I’m really impressed with what you’re putting together here in terms of shows, the way you hang the art,’ he said okay, so he put me out and after a couple weeks, I even got a paycheck. So that was the start of my good relationship with the Institute.

Sorry to bring us to the sad part of the interview, but when did when did Bodega close?

1965 or so. Joe Piazza gave me a 30-day notice because Bud Hershfield had a wallpaper paint store right next door to Café de Napoli. And Bud needed extra space for storage, and he talked Joe into renting my space to him. So Joe gave me the notice and I had to move out. We had a huge sale; Star Tribune did a big piece on it. Everybody came down. It turned out to be a fun night. But at the time I thought it was the end of the world. Losing my lease, losing the gallery. In reality, it was one of the best things that ever happened to me, because I went to California and found this whole new life and created really fun things. The first thing I did when the gallery closed was drive down to the coast to see Michael Blodgett, who was my best friend in high school.

Blodgett was now in Hollywood and had become quite famous as an actor. When we got there, Blodgett was working on a film with Jack Nicholson; a Roger Corman film, The Trip. And they had a couple of dancers in a scene that they wanted to have painted. Blodgett convinced the directors that I had some paint that was flexible I could use to body paint these girls. So, I “invented” a flexible paint. I went into the set and I painted these dancers and they loved it. They hired me the first week I was in California to paint these girls and I figured it wasn’t such a bad place to be, this is a fun place, and I wanted to stay there. I had planned to stay just for a couple weeks; I ended up staying 30 years.

Blodgett was my biggest supporter in California; whenever he did a film or a TV show, he would convince the showrunners to get me on there. I was always the art director or something of that caliber. But I got a lot of jobs that way and I became quite well known as an art director. And the rest is history.

As a Midwest native who made his way out to the West Coast and then onto Maui, is there any parting wisdom you would leave to the Minneapolis art scene today?

Four things were important to me: Mentors, muses, partners and apprentices. But especially mentors. Mentoring and being mentored. I get a lot of interns form the University of Cincinnati or Art Center LA and even Germany, people come here and work with us for three to six months, and that’s the thing I try to tell them; it’s really important to have mentors. You can’t necessarily do it all by yourself. Sometimes you need a role model. You’ve got to have somebody like I had Duchamp. Patting me on the back, telling me I’m great. Encouraging me. And muses, you need to have someone like Olivia [Tom’s current assistant], Rita, or some of the interns to inspire you with new ideas. Partnerships are wonderful. I’ve got a lot of great partners, and my wife is my best partner, so it’s important to have. And you need someone to mentor, to pass your legacy onto, someone who will hold your memory. If you don’t, if you go through life and you don’t have any of that, you have a hard row to hoe. It’s difficult. Without those four relationships, what is life?